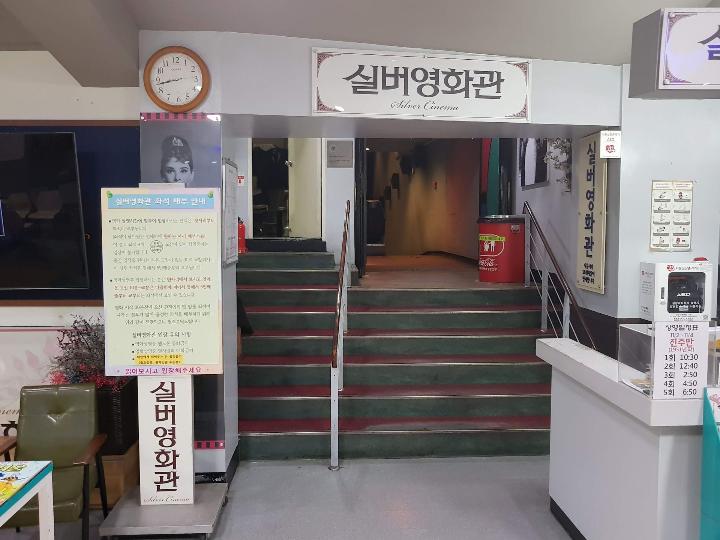

In a quiet corner of central Seoul, inside the historic Nagwon Instrument Arcade, 80-year-old Jung Jung-kyu makes his daily pilgrimage. He travels an hour from Hanam to reach the Silver Cinema, where for just 2,000 won (roughly $1.45), he can watch classic films, meet friends, and escape into the nostalgia of movies that shaped his youth. “With just 2,000 won, I can meet my friends here and watch movies. What better place can I have this fun at this cost?” he told The Korea Times last year.

Jung’s story is becoming increasingly common across the globe as cinema exhibitors wake up to a demographic reality that has profound implications for the industry: the world is getting older, and the cinema business needs to adapt to meet their needs.

Seoul’s “Anyone’s Youth Stage”: A Model for the Future

The Seoul Metropolitan Government announced this week that it will transform its senior-only “Youth Theater” into a participatory cultural space called “Anyone’s Youth Stage.” Originally established in 2010 in the Munhwa Ilbo Hall in Jung-gu, the venue supported seniors aged 55 and older to watch films and performances at subsidiced rates. Following the expiration of its private consignment period in December 2025, the facility is being reimagined as something far more ambitious.

The pilot programme, running until the official March launch, combines morning interactive sessions - including Nanta percussion classes and singing workshops - with afternoon screenings of domestic and international films. All activities are free of charge. Kim Tae-hee, head of Seoul’s Cultural Affairs Bureau, described the vision as “a warm cultural space where seniors who lack leisure and cultural opportunities can stay comfortably and enjoyably.”

This evolution from passive consumption to active participation represents a broader shift in how exhibition spaces are thinking about their role in communities - particularly for older audiences.

The Demographic Imperative

The numbers are stark. According to the United Nations, the global population aged 65 and older is projected to more than double from 830 million today to 1.7 billion by 2054. By the late 2070s, people over 65 will outnumber children under 18 worldwide. Asia stands at the epicentre of this transformation, with Hong Kong, South Korea, Taiwan, and Japan expected to see approximately 40 per cent of their populations aged 65 and older by 2050.

South Korea itself is projected to become a “super-aged” society by 2025, with one in five citizens over 65. Japan already has nearly 30 per cent of its population in that bracket. These are not merely abstract statistics for demographers to ponder; they represent a fundamental reshaping of the potential audience for theatrical exhibition.

For an industry that has long skewed its marketing, programming, and pricing toward younger demographics, this shift demands a strategic rethink. The teenagers who queued for blockbusters in the 1970s and 1980s are now in their 60s and 70s - and they haven’t lost their love of cinema.

Silver Screenings: More Than Discount Tickets

Across the United Kingdom, exhibitors have developed robust programmes targeting older audiences. ODEON’s “Silvers” programme offers early bird showtimes for guests over 60, with tickets from £3 including complimentary tea, coffee, and biscuits. Showcase Cinemas runs “Silver Screenings” every Monday, with discounted tickets for seniors on films showing before 4pm, accompanied by a hot drink and snack offer.

Picturehouse cinemas offer their “Silver Screen” programme at locations across England and Scotland, providing over-60s with discounted tickets and free tea or filter coffee. The Light cinema chain’s “Silver Screen” at New Brighton offers £5 tickets for guests over 60 before 3pm every Thursday.

But the value of these programmes extends far beyond price. The social element—the cup of tea before the film, the opportunity to chat with fellow cinema-goers—addresses something that health researchers have identified as a crisis among older populations: loneliness.

Cinema as Social Medicine

Research from Johns Hopkins School of Medicine has found that social isolation carries health risks comparable to smoking 15 cigarettes daily, with roughly one in four people over 65 experiencing social isolation. The World Health Organisation has recognised social isolation and loneliness as priority public health problems, establishing a Commission on Social Connection to address the issue through 2026.

A 2024 scoping review published in BMC Geriatrics found that nearly 20 per cent of older adults in the European Union live alone, with cultural shifts toward individualism and the fragmentation of traditional community-based living arrangements exacerbating isolation. The consequences are severe: increased risks of depression, cognitive decline, and mortality.

Against this backdrop, the cinema’s role as a community gathering space takes on renewed significance. Professor Park Seung-hee of Sungkyunkwan University, speaking about Seoul’s Silver Cinema, observed that “engaging in enjoyable activities promotes happiness, which in turn reduces the risk of illness, boredom and loneliness. This creates a positive cycle.”

The Strand Arts Centre in Belfast has taken this philosophy to heart, offering Silver Screenings with free transport for community groups and nursing homes. “Belmont Bowling Club is accessible, has free parking and a spacious warm screening room,” the centre notes, emphasising the practical considerations that make attendance possible for those with mobility limitations.

Dementia-Friendly Cinema: A Growing Movement

Perhaps the most significant development in senior-focused exhibition has been the growth of dementia-friendly screenings. In 2017, the Alzheimer’s Society and the BFI Film Audience Network joined forces with the UK Cinema Association to produce guidance for cinemas introducing these programmes. Since then, what began as a niche offering has become a significant feature of exhibition calendars.

With more than 900,000 people in the UK currently living with dementia (a figure projected to reach over two million by 2050) the need is evident. Dementia-friendly screenings involve subtle but meaningful adjustments: dimmed rather than dark auditoriums, lowered volume levels, relaxed attitudes toward movement and noise, clear signposting, no trailers, optional intervals, and staff trained as Dementia Friends through the Alzheimer’s Society initiative.

Sheffield’s Showroom Cinema exemplifies best practice, offering monthly dementia-friendly screenings at £5 per ticket in association with the Alzhiemer’s Society. The programme includes clear signage throughout the venue, prompt start times with no advertisements, reduced capacity, unallocated seating for free movement, and a 10 per cent café discount on screening days.

In Australia, the National Film and Sound Archive has launched “A Day at the Movies,” a three-year dementia-friendly screening programme developed by UNSW researchers. The initiative features morning teas, intervals, designated quiet spaces, and refreshments - recognising that the cinema experience extends well beyond the film itself.

As Dr Jodi Brooks of UNSW observed: “Going to the cinema is always about more than just the film itself. The programme will create meaningful social opportunities for people living with dementia, through morning teas, intervals and the creation of an associated film group.”

The Power of Nostalgia

Film selection plays a crucial role in these programmes. The Alzheimer’s Society notes that musicals can be particularly engaging for people with dementia, as the brain processes music differently from other functions. “’Grease’ can still be enjoyed after other activities become more difficult,” their guidance explains.

The Plaza Cinema in Stockport staffs its dementia-friendly screenings with trained Dementia Friends and programmes “a combination of classic movies, musicals and archive films specially selected to trigger memories.” Oxford’s Ultimate Picture Palace runs a “Meet Me at the Movies” programme that has screened classics like “Singin’ in the Rain” (1952) and “The Wizard of Oz” (1939).

Seoul’s Silver Cinema (where all these photos are from) takes this approach to its logical conclusion, screening exclusively classic Hollywood and Korean films from the 1940s through 1960s. When “Ben-Hur” (1959) appears on the programme, all 300 seats regularly sell out. The films and songs we have loved, as one researcher put it, are “powerful repositories of memory.”

Accessibility Beyond Age

The push for senior-friendly exhibition intersects with broader accessibility improvements that benefit audiences with hearing and visual impairments - conditions that become more prevalent with age. Research from Johns Hopkins found that hearing loss is associated with a 28 per cent greater risk of social isolation over time.

Modern cinema accessibility technology has advanced considerably. Audio description tracks, stored as channel 8 on Digital Cinema Packages, provide narrated information about visual elements for blind and partially sighted audiences. Hearing loops transmit sound directly to hearing aids equipped with telecoils. Closed captioning devices like Watch Word (offered by CinemaNext in the UK) superimpose text over the film for individual viewers without affecting others in the auditorium.

In March 2024, India’s Ministry of Information and Broadcasting introduced guidelines requiring accessibility features - including audio description, closed captioning, and Indian Sign Language - for all new theatrical releases. This regulatory approach signals growing recognition that accessibility is not merely a nice-to-have feature but a legal right.

The CEA Card scheme in the UK, accepted at approximately 90 per cent of cinemas including Cineworld, ODEON, and Vue, allows those receiving disability benefits to obtain free admission for an accompanying carer. Such practical measures can make the difference between cinema attendance being possible or not.

The Business Case

The commercial logic for embracing older audiences is compelling. Silver screenings typically occur during off-peak hours - weekday mornings and early afternoons - when auditoriums would otherwise sit empty. The concession spend may be lower (a cup of tea rather than a bucket of popcorn), but the alternative is often zero revenue.

More significantly, as traditional younger demographics increasingly have entertainment options competing for their attention - from streaming services to gaming - older audiences represent a stable, loyal customer base with time to spare and, often, disposable income to match. They are also less price-sensitive than teenagers and more likely to appreciate the theatrical experience as an event worth leaving home for.

Australia’s Event Cinemas has recognised this with its “Cinebuzz for Seniors Rewards Club,” offering exclusive screenings, points toward free movies, and special senior screenings with complimentary morning tea. The programme transforms occasional visitors into regular patrons.

Challenges and Considerations

Not all trends point positively. ODEON has removed its general senior and student discount tickets as part of a “simplified pricing structure,” though it maintains the Silvers programme.

Professor Park of Sungkyunkwan University noted that while senior cinemas provide valuable community spaces, they also highlight the limited leisure options available to many older adults.

“This current older generation, I say, is the most unhappy generation as they don’t know how to enjoy their extended lives,” Park observed, calling for more government support for programmes that enable older adults to engage fully in cultural life.

Transport remains a significant barrier. The Strand Arts Centre’s offer to cover transport costs for nursing homes and community groups acknowledges a practical reality: even a subsidised ticket is worthless if you cannot get to the cinema. As populations age, solutions that combine transport, accessibility, and social programming will become increasingly important.

Looking Forward

The transformation of Seoul’s Youth Theater into “Anyone’s Youth Stage” represents something more than a municipal facilities upgrade. It signals a recognition that cultural spaces serve purposes beyond content delivery; they are gathering places, community hubs, and spaces for human connection.

As global populations age, exhibition businesses that understand this will find themselves serving a growing and loyal audience segment. Those that continue to focus exclusively on younger demographics may find themselves with increasingly empty auditoriums.

Back in Seoul’s Nagwon Arcade, 89-year-old Lee Young-jik makes a three-hour journey from Yongin to meet friends at the Silver Cinema. He worked hard his entire life and never had time for movies when he was younger. Now, in his twilight years, he has found a place where he belongs.

The cinema industry would do well to ensure there are more places like it.

[All photos of the Silver Cinema in Seoul taken by Patrick von Sychowski at a fact-finding trip to Korea with Germany's Cineplex Group in 2018.]

The Silver Screen Renaissance: How Cinemas Are Embracing Older Audiences